Offering an incredible insight into the history of South Africa

The Battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal offer an incredible insight into the history of South Africa. The most 'famous' battles are the Battle of Isandlwana, the Battle of Rorke's Drift, the futile Battle of Spionkop, and the Battle of Blood River.

The best way to really appreciate the bloody and fiercely-fought battles that took place here is to go on one of the mesmerising and theatrical tours of the key areas.

These are not your usual dry reports, of interest only to military historians - these are incredible stories of events that happened less than 150 years ago and the impact they had on those directly involved and the world at large.

No matter how uninterested you think you are in history, these tours will captivate and move you, and a 2 night stay in this area is a highly recommended addition to anyone's itinerary.

With a range of accommodation options to suit all budgets, this is an easy add on to any itinerary including a stay in KwaZulu-Natal, and can easily be combined with the region's other highlights, including the beach, game reserves and the magnificent Drakensberg Mountains.

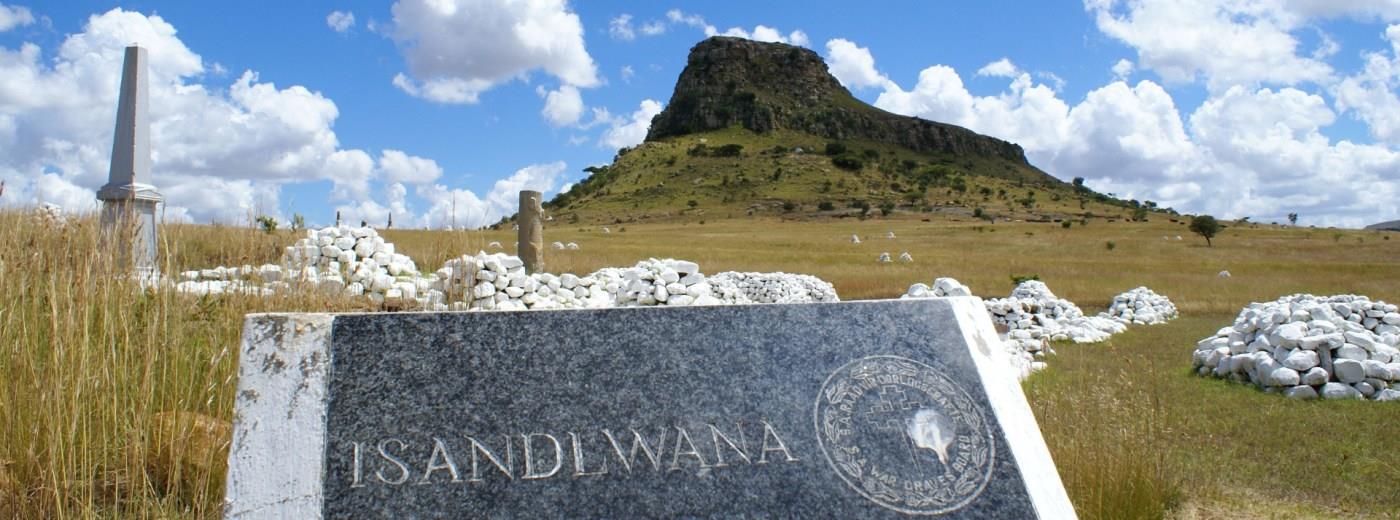

The Battle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu war between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom.

A 20,000 strong Zulu army attacked the heavily armoured but far smaller British Army contingent of 1,774 men on the morning of 22nd January 1879. Despite many tales of individual heroics, only a handful of British soldiers escaped alive after a fierce 2 hour battle, and this massacre was the British Army's worst defeat in Africa. The battle site itself is a eerie and haunting place, and both the Zulu and British view the events of that day as a tragedy.

One of the gravest errors made by the commander of the British force, Lord Chelmsford, when setting up the British army camp at Isandlwana a couple of days before the battle, was to not entrench his army's position at Isandlwana or encircle the wagons, which left the camp with no meaningful defences. Chelmsford believed that his army, with their rifles and field guns, were more than a superior match against a force equipped mainly with assegai spears, cow-hide shields and few muskets/rifles - so as a result was more concerned about planning his forward advance rather than defending against a possible attack. This severe underestimation of the Zulus' capabilities was to be one of the major contributing factors to the ensuing defeat.

When most of the 20,000 Zulu warriors were discovered hiding in a nearby valley by a British scouting party early on the morning of 22nd January, the Zulus immediately advanced and went straight on the offensive. They attacked using their traditional 'horns and chest of the buffalo' formation and quickly began to encircle the British camp.

The British forces fought valiantly, and managed to hold off the centre of the main force with their superior firepower and partillery, inflicting many casualties. However as the battle wore on, the rate of fire began to drop as the soldiers began to tire and the Zulus slowly advanced. At this point throughout the battle, the British fought back to back with bayonet and rifle until completely spent and fierce hand to hand combat ensued. The Zulus, far superior in numbers, overwhelmed them and no mercy was given.

The battle truly stunned the world as it was unthinkable that a 'native' army could completely wipe out such a heavily armoured battalion of troops.

Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke’s Drift started immediately after the British Army had been defeated at the Battle of Isandlwana, and continued into 23rd January. Also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, it is the story of when some 150 British soldiers and colonial troops defended a supply station against approximately 4,000 Zulu warriors. Over 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded. It is truly a story of great courage.

Led by Lieutenants John Chard of the Royal Engineers and Gonville Bromhead, it was decided that a retreat was out of the question, as the quick and mobile Zulu forces would have easily overtaken such a small column, and so it was soon agreed that the best course of action was to stand their ground.

After a defensive perimeter had been established that included the station's store house, field hospital and stone kraal, the garrison was soon reinforced by around 100 cavalrymen of the Natal Native Horse (NNH), leaving Chard with a force of nearly several hundred men, enough in his mind to hold off the Zulu force.

The battle began at 16:20 with the NNH briefly engaging the Zulu’s vanguard before retreating and leaving the garrison severely depleted. Soon after, around 600 Zulus attacked the south wall which included the hospital and the storehouse, with both forces soon engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat. After a period of intense fighting, the battle began to take its toll, and it soon became clear that the hospital and north wall could not be held. The order was given for the garrison to fall back.

Soldiers holding the hospital with rifles and bayonets had to escape by hacking their way through the walls, all the while fighting for their lives and holding off the furious attack of the Zulus, and at the same time trying to get their own wounded men to safety. On top of all of this, they had to contend with fact that the hospital by now was ablaze. Battered, bloodied and despite being under constant attack at close quarters, the soldiers managed to clamber through a window and make it to the barricade.

As night fell, the unrelenting Zulu attack intensified, forcing the remaining British troops to again to fall back and form a bastion around the storehouse. This assault continued into the night, only ending at 02:00, to be replaced by a constant fire from Zulu guns. At this point in time the defending forces were exhausted, wounded and had been fighting for nearly 10 hours. Their ammunition was all but spent, with reports saying that of the 20,000 rounds the British had, only 900 were left, and dawn was fast approaching.

As the sun began to rise, the British garrison prepared for another attack but were not greeted by one, instead, they witnessed a sight that took them by total surprise - the Zulus were gone. As reinforcements arrived, this marked the end to one of the most incredible defenses undertaken by such a small force in the face of overwhelming odds.

Spionkop

The focal point of the second major war between the British and Boers (now referred to as the South African war) was the 118 day siege of the British town of Ladysmith in Natal. Whilst the story of the siege is fascinating in its own right, it is the events that occurred at Spionkop as the British tried to get support to Ladysmith that are really moving.

On 23rd January 1900, 1,700 British troops (part of a British force of 24,000 heading for Ladysmith) took over this small hill, and were attacked the next day by 3,600 Boers. Poor communication meant that the British force was not reinforced from the main party, and in the ensuing battle, many hundreds of British and Boer soldiers were killed and wounded. By the middle of the following night, both sides believed they had lost and retreated, leaving the hill to the dead and the dying. Several hours later the Boers returned, and finding the hill deserted, reclaimed it.

The futility of war has never been so movingly illustrated, and to add to the sense of international significance Winston Churchill, Mahatma Ghandi, and Louis Botha (first President of the independent South Africa) where all present on the hill on that day. Had any one of them been killed, the 20th century would have been very different.

The Capture and Escape of Winston Churchill

Also taking place later during the long siege of Ladysmith, the young Winston Churchill, at the time a war correspondent for the Daily Mail and Morning Post, was travelling by train with British soldiers, when it was attacked by force of Boer commandos who successfully caused the train to crash.

The soldiers began to return fire and battle ensued. After 70 minutes of fighting, the Boars overwhelmed the British, taking a number of prisoners in the process.

Churchill himself found himself in a nearby gully, exhausted by the fighting and midday heat. He was then discovered by one of the Boers - Louis Botha, the future Prime Minister of South Africa. Instinctively, Churchill went for his pistol, only to find an empty holster instead - leaving him with no other option but to surrender.

Churchill and a number of other POWs were transferred to Pretoria, the then capital of the Boer Transvaal Republic, and imprisoned in a converted school in the middle of the city. Four weeks later, however, Churchill escaped captivity, and with a bit of luck and plenty of courage, he made his way to the railway line and headed east until he reached Mozambique and safety. After establishing his identity with the local British Consul, Churchill travelled back to Durban where a hero's welcome greeted him.

The Battle of Blood River

In February 1838, the Boer trek leader, Piet Retief, met with Dingane, the Zulu chief, to agree to the purchase of a large tract of Zulu land for the establishment of an independent Boer nation. Dingane agreed to the deal, however, after the signing of a title deed Dingane then ordered the slaughter of Retief and the party of men who accompanied him. The Battle of Blood River was the Boers revenge for this treachery. On 15 December 1838, led by Andries Pretorius, a 464 strong Boer army marched out, and made a D-shaped formation with 64 wagons at Ncome River and waited for the Zulus to attack.

The next morning, 10,000 Zulus had surrounded them, but were driven off by fierce gun fire and a mounted charge. After 3 hours, the river ran red with the blood of 3,000 massacred Zulus. Only 3 Boers were wounded.

Today, the 16th December is still commemorated, now as a Day of Reconciliation, and 64 bronze wagons mark the site of the battle. Near the Boer monument a Zulu Monument and museum tell the story from a different perspective.